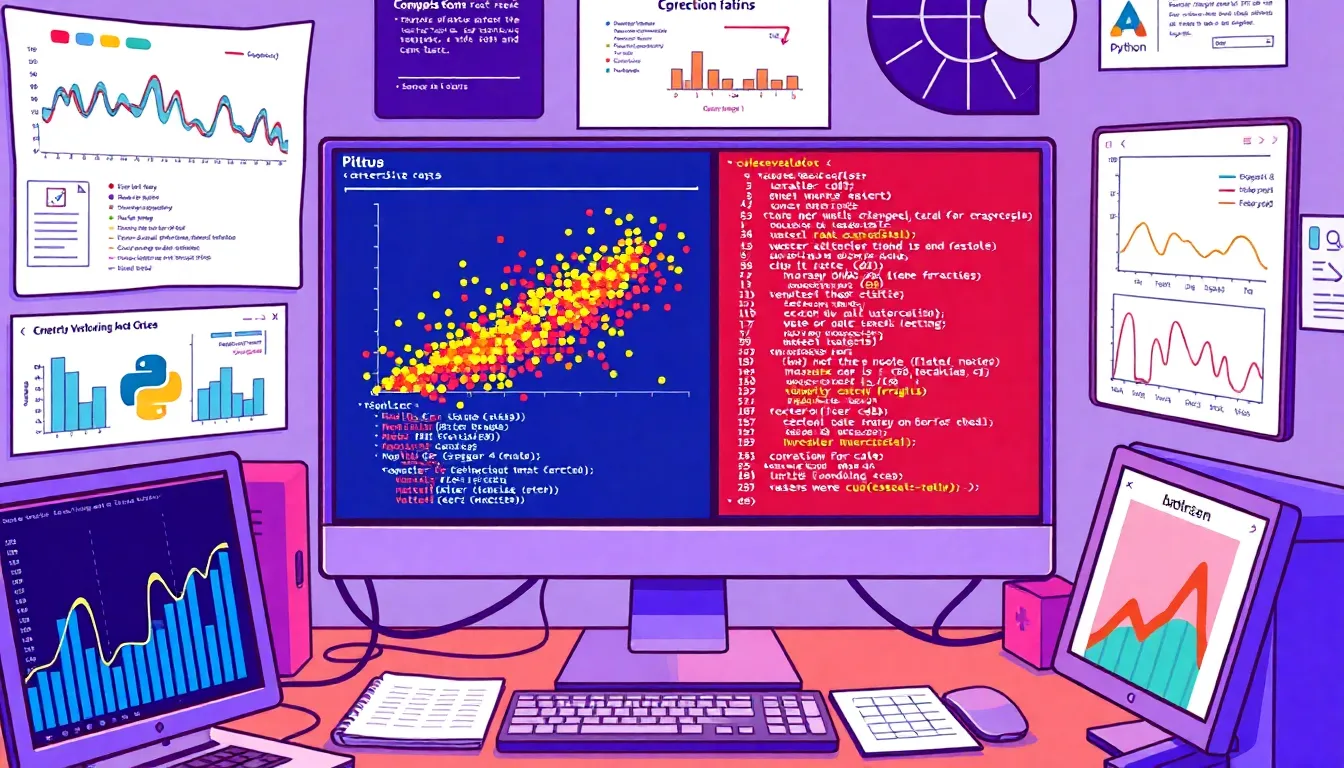

Cross-validation is a critical technique in machine learning used to assess how a model will generalize to an independent dataset. Think of it as a way to ensure your model isn’t just memorizing the training data but is instead learning to make predictions on unseen data. There are several strategies you can employ, each with its own pros and cons.

The simplest method is the holdout method. Here, you split your dataset into a training set and a testing set. For instance, you might use 80% of your data for training and 20% for testing. The downside is that you’re only using a portion of your data to train the model, which can lead to high variance in performance.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split # Assuming X is your feature set and y is your target variable X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

Another common approach is k-fold cross-validation. This technique involves dividing the dataset into ‘k’ subsets and then training the model ‘k’ times, each time using a different subset as the test set while using the remaining data for training. This method helps reduce variance by ensuring that every data point gets to be in a training and test set.

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold

kf = KFold(n_splits=5)

for train_index, test_index in kf.split(X):

X_train, X_test = X[train_index], X[test_index]

y_train, y_test = y[train_index], y[test_index]

# Train your model here

Stratified k-fold cross-validation is a variation that can be particularly useful when dealing with imbalanced datasets. It ensures that each fold maintains the same proportion of classes as the complete dataset, which can lead to more reliable performance estimates.

from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedKFold

skf = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5)

for train_index, test_index in skf.split(X, y):

X_train, X_test = X[train_index], X[test_index]

y_train, y_test = y[train_index], y[test_index]

# Train your model here

Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) is an extreme case of k-fold where k is equal to the number of data points in the dataset. Every single observation is used for testing, while the remaining observations are used for training. This method can be computationally expensive, especially for large datasets, but it provides a very thorough evaluation.

from sklearn.model_selection import LeaveOneOut

loo = LeaveOneOut()

for train_index, test_index in loo.split(X):

X_train, X_test = X[train_index], X[test_index]

y_train, y_test = y[train_index], y[test_index]

# Train your model here

Choosing the right cross-validation strategy often depends on the size of your dataset, the computational resources you have, and the specific characteristics of your data. Each method offers trade-offs, and understanding these will help you make more informed decisions as you develop your models.

One common pitfall is not accounting for data leakage, where information from the test set inadvertently influences the training process. This can lead to overly optimistic performance metrics and a model that performs poorly on real-world data. Always ensure that your data splitting strategy maintains the integrity of your test data.

Another issue is the computational burden that comes with strategies like LOOCV or even k-fold cross-validation with a large number of folds. Depending on your model complexity, this can lead to excessively long training times, so balancing thorough validation with efficiency is key.

In addition, ensure that you’re not overfitting to your validation folds. It’s tempting to tune your model based on the performance across the folds, but that can lead you to a model that doesn’t generalize well. Instead, hold out a separate validation set or use techniques like nested cross-validation to mitigate this risk.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Another pitfall to watch out for is the misinterpretation of cross-validation results. It’s important to remember that the performance metrics you obtain from cross-validation are estimates of how your model will perform on unseen data. If you’re not careful, you might take these estimates at face value without considering their variability, especially in smaller datasets. Always report the mean and standard deviation of your cross-validation scores to provide a clearer picture of model performance.

In addition, using the same random seed for your splits can lead to biased results. While it may seem convenient to set a fixed state for reproducibility, it can also mask the variability in model performance. Consider running your cross-validation multiple times with different random seeds and averaging the results to get a more robust estimate.

Another common oversight is failing to properly shuffle the dataset before performing cross-validation. A non-random order of data can introduce bias, especially if there are underlying patterns in the data sequence. Always shuffle your dataset before splitting to ensure that your validation folds are representative of the overall dataset.

When working with time series data, standard cross-validation techniques can yield misleading results due to the temporal dependencies in the data. In such cases, it’s better to use techniques like time series split, which respects the chronological order of the data and prevents future information from leaking into the training set.

from sklearn.model_selection import TimeSeriesSplit

tscv = TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=5)

for train_index, test_index in tscv.split(X):

X_train, X_test = X[train_index], X[test_index]

y_train, y_test = y[train_index], y[test_index]

# Train your model here

Lastly, be cautious of the computational resources required for cross-validation. Depending on the complexity of your model and the size of your dataset, you may need to consider parallel processing or using more efficient algorithms to avoid long training times. Libraries such as joblib can help you parallelize your cross-validation process effectively.

from joblib import Parallel, delayed

def train_model(X_train, y_train):

# Your model training code here

pass

results = Parallel(n_jobs=-1)(delayed(train_model)(X[train_index], y[train_index]) for train_index in kf.split(X))

Understanding these pitfalls and how to navigate them will not only improve your model’s performance but also enhance your overall workflow in machine learning. The key is to remain vigilant and always question your assumptions while validating your models.